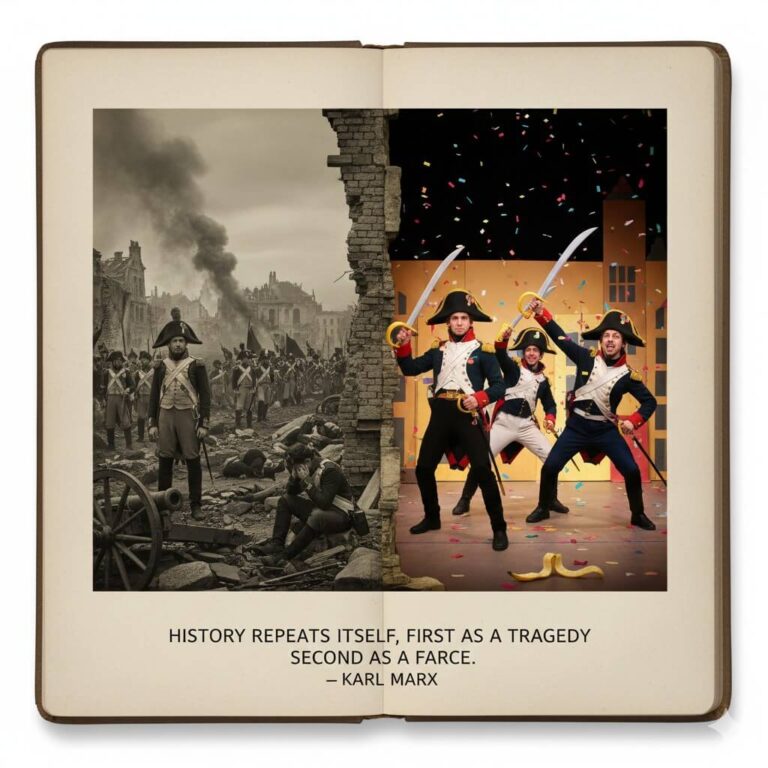

“History repeats itself, first as a tragedy, second as a farce.” When Karl Marx wrote this line in 1852, he was watching France make the same mistake twice. Napoleon Bonaparte had once risen to power in a dramatic and world-changing way. Years later, his nephew copied that rise—but without the brilliance or depth. What had once been serious and powerful now looked shallow and almost embarrassing. Marx was pointing to something deeply unsettling about human societies: we keep repeating our mistakes, and each time we do, the repetition feels less serious—even though it still causes real harm.

For us in India, this idea feels uncomfortably close to home. Our history is full of such repetitions—events that return again and again, losing their dignity but not their ability to hurt people.

To understand Marx’s thought, we first need to understand the difference between tragedy and farce. A tragedy is heavy and serious. It shocks us. When something terrible happens for the first time, people are stunned. Even if there were warnings, the full impact feels unreal until it arrives. The pain is deep, and the memory stays with us. A farce, on the other hand, feels almost absurd. When the same event happens again, we are no longer shocked. We recognize the signs. We know how the story will end. What makes it farcical is not that the suffering disappears, but that we allow it to happen despite knowing better.

Why does repetition make things feel ridiculous? One reason is that surprise is gone. Another is that the context has changed, making old actions look empty. But the main reason is simple: repeating the same mistake twice feels foolish. The first time, ignorance might be an excuse. The second time, it becomes a choice.

Few examples show this more painfully than India’s history of famine. The Bengal Famine of 1943 remains one of the darkest moments in our past. Around three to four million people died. This did not happen because India lacked food. It happened because of cruel and careless policies. The British colonial government cared more about the Second World War than Indian lives. Grain was stored or exported, prices rose sharply, and distribution collapsed. When Winston Churchill was informed, he reportedly made cruel remarks about Indians and questioned why Gandhi was still alive. Villages were emptied. Families disappeared. The sight of starving bodies on Calcutta’s streets burned itself into the nation’s memory. This was not a natural disaster—it was a man-made tragedy that showed how little Indian lives mattered under colonial rule.

After independence, it seemed impossible that such a horror could happen again. Surely, we had learned. We understood that food security is not just about growing food but about sharing it fairly. We knew that governments must act quickly and value every life. And yet, history echoed. In 1966, Bihar faced a severe famine-like crisis. Food production fell, systems failed, and millions were again pushed to the edge. This time, there was no foreign ruler to blame. These were our own systems, our own mistakes. Similar food crises followed in other regions over the years. Every time, the same weaknesses showed up: hoarding, slow administration, poor coordination, and failure to reach those who needed help most.

This is where Marx’s idea fits painfully well. These later crises still caused real suffering, but they also began to feel strangely familiar—almost staged. Grain would rot in government warehouses while people went hungry nearby. Politicians would visit affected areas for photographs. Committees would be formed. Reports would be written. Promises would be made. Everyone would say, “Never again.” And yet, the cycle would return. The problem was not lack of knowledge. We knew what had gone wrong in 1943. We had resources. We had democracy. What made it farcical was the gap between what we knew and what we did.

The bureaucratic response became predictable to the point of absurdity. Files moved slowly while stomachs stayed empty. Officials debated rules while children suffered from hunger-related diseases. The language of a caring, socialist India clashed sharply with the reality of ration lines and shortages. Each crisis followed the same rhythm: denial, delayed action, short-term relief, and then silence—until the next crisis arrived.

But India’s story does not end there. Unlike Marx’s darkest warning, we eventually did break this particular cycle. The Green Revolution, despite its flaws, changed India’s food situation. The country moved from scarcity to surplus. Systems like the Public Distribution System created some protection for the poorest. Movements demanding the Right to Food pushed the idea that eating is not charity but a basic right. Laws like the National Food Security Act tried to make governments accountable. Progress was slow and uneven, but it happened. Famines, which had haunted India for centuries, are no longer a regular threat. This shows that history does not have to repeat forever—if we choose to learn.

Still, Marx’s warning remains relevant in many other areas of Indian life. Communal violence follows a familiar pattern: hateful speeches, sudden violence, silence from those in power, calls to forget and move on—until it happens again. Dynastic politics continues despite public frustration, with each generation often appearing less capable than the last. Corruption scandals unfold like reruns: exposure, anger, promises of investigation, fading headlines, and quiet return to normalcy. Each time, people react with anger mixed with tired recognition. We know this story too well.

The real danger is not repetition itself, but comfort with repetition. When events become familiar, we stop resisting them. We become observers instead of participants. We may joke about how predictable everything is, but that humor hides a deeper helplessness. Knowing what will happen next does not automatically give us the strength to stop it.

Marx’s line is not just a clever observation. It is a warning—and also a lesson. India’s experience with famine shows both sides of it: how mistakes repeat, and how cycles can eventually be broken. Awareness alone is not enough. Memory must be followed by action. Political will must match knowledge. Only then can we honor past tragedies by ensuring they are not replayed as tomorrow’s farces. History does not move forward on its own. We have to push it.